Growth Without Transformation in Africa

Evidence from Growth Accelerations, Economic Complexity, and Institutions

Growth Without Transformation in Africa: Evidence from Growth Accelerations, Economic Complexity, and Institutions

Robert Kappel

The Working Paper Growth Accelerations and Transformation

in African Countries https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-107094-5 provides an empirically grounded reassessment of Africa’s development trajectory between 2000 and 2024. Contrary to optimistic narratives portraying Africa as a “rising” or “future” continent, the evidence reveals a far more sobering picture. While selected countries have achieved periods of rapid growth and modest structural change, most African economies remain trapped in volatile growth patterns, low industrialisation, weak integration into global value chains, and persistent institutional fragility.

Using three complementary analytical lenses—growth accelerations, economic complexity, and multidimensional performance—the paper demonstrates that Africa’s core development challenge is not the absence of growth per se, but the failure to transform growth into sustainable, productivity-driven development. Genuine growth accelerations, as defined by Hausmann, Pritchett, and Rodrik, are rare and fragile. Most growth episodes were driven by external commodity booms, public investment surges, or post-conflict reconstruction, rather than by deep structural transformation.

The Economic Complexity Index reveals a fundamental structural constraint. With few exceptions, African countries remain at very low levels of productive complexity, heavily dependent on raw materials and low-value exports. Even countries with comparatively strong performance—such as Tunisia and Morocco—struggle to generate sufficient productive employment, highlighting the limits of partial industrialisation in a highly competitive global environment.

Recent evidence on industrialisation confirms these findings. Manufacturing value added remains low or declining across most of the continent, and Africa’s integration into global value chains is shallow, concentrated in low-value segments with limited local spillovers. Industrialisation has not functioned as a self-sustaining engine of growth, employment, or learning.

Institutional performance further explains this pattern. The Performance Index Africa shows that many countries significantly underperform relative to their income levels, reflecting extractive institutions, rent-seeking elites, and declining state capacity. Demographic pressures amplify these constraints: rapid population growth far exceeds the capacity of African economies to create productive jobs, while small and medium-sized enterprises remain too small, informal, and weakly connected to scale up.

The paper concludes that Africa’s development challenge is largely self-inflicted. Despite progress in governance, infrastructure, and poverty reduction in selected countries, the continent has not overcome the structural, industrial, and institutional barriers required for sustained transformation. Without decisive progress in building productive capabilities, strengthening inclusive institutions, and expanding industrial and value-adding activities, Africa risks remaining a continent of unrealised potential rather than one of convergence.

1. Africa Between Hope and Reality

Over the past three decades, Africa has been framed by sharply contrasting narratives. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the continent was widely portrayed as a “hopeless continent,” characterised by state failure, conflict, economic collapse, and mass poverty. By the early 2010s, this image had shifted dramatically. Africa was rebranded as a “rising” or even “future” continent, driven by high growth rates, commodity booms, demographic dynamism, expanding markets, and increasing foreign investment.

Both narratives[1] suffer from the same analytical flaw: they treat Africa as a homogeneous entity. Empirical evidence since 2000 demonstrates that Africa is not converging toward a common development path. Instead, the continent has undergone a process of structural divergence, with countries following fundamentally different trajectories shaped by political institutions, state capacity, economic structure, and demographic pressures.

Between 2000 and 2014, Africa experienced its strongest growth phase since independence. Average GDP growth exceeded 5 percent, and per capita incomes rose modestly in many countries. This period often labelled “Africa Rising,” coincided with a global commodity supercycle, rising Chinese demand, debt relief, and improved macroeconomic management. However, after 2015 this momentum dissipated. Growth slowed sharply, per capita incomes stagnated, and poverty began to rise again in several large economies and fragile regions.

Looking at the full period from 2000 to 2024, average annual real GDP per capita growth across Africa was only about 1.1 percent. Over a longer horizon, Africa lost ground relative to all other world regions. Only a handful of countries achieved sustained per capita growth above 3 percent, while the majority experienced stagnation or repeated reversals. These outcomes challenge both the earlier pessimism and the later optimism. Africa is neither uniformly failing nor uniformly rising; it is fragmenting into a small group of partial transformers and a large group of countries that remain structurally stuck.

This paper argues that the central question of African development is therefore not whether growth occurs, but whether growth translates into structural transformation. To address this question, the analysis applies three complementary lenses: growth accelerations, economic complexity, and multidimensional performance. Together, these indicators reveal why progress has been limited, why volatility persists, and why many African economies remain unable to convert growth into durable development.

2. Growth Without Transformation: Evidence from Growth Accelerations

Standard growth statistics obscure the episodic and fragile nature of Africa’s economic expansion. The concept of growth accelerations, developed by Hausmann, Pritchett, and Rodrik[2], offers a more precise way to distinguish between short-lived booms and genuinely transformative growth episodes. Growth accelerations are defined as sustained and significant increases in real per capita income that persist over many years and generate lasting level effects.

Applying this framework to African data between 2000 and 2024 yields a clear result: true growth accelerations are rare. Only a small number of countries—most notably Rwanda, Ethiopia (until 2015), and Côte d’Ivoire—experienced multi-year periods that come close to meeting the strict criteria of sustained acceleration. Even fewer managed to institutionalise these episodes and protect them from political or external shocks.

For most African economies, growth followed a different pattern. During the commodity boom, output expanded rapidly, but this expansion was largely driven by external demand, rising prices, and public investment rather than by productivity gains or structural change. Once commodity prices fell after 2014, growth collapsed in many countries. Nigeria, Angola, Zambia, and South Africa illustrate this pattern: periods of expansion were followed by stagnation or decline, with little lasting improvement in living standards.

The volatility of growth is further amplified by demographic dynamics. Population growth rates of 2–3 percent per year absorbed much of the aggregate expansion. As a result, even relatively high GDP growth translated into modest or negligible per capita gains. After 2015, per capita income growth across the continent fell close to zero, and in some countries turned negative.

The key implication is that growth in Africa has been largely decoupled from transformation. Growth accelerations were often triggered by favourable external conditions or state-led investment drives, but they were not sustained by diversification, industrial upgrading, or institutional consolidation. When political fragmentation increased or external conditions deteriorated, growth stalled. This explains why Africa’s post-2015 slowdown represents not merely a cyclical downturn, but the exposure of unresolved structural weaknesses.

3. Low Economic Complexity and the Absence of Industrial Deepening

The Economic Complexity Index provides a structural explanation for Africa’s limited capacity to sustain growth. Economic complexity measures the diversity and sophistication of a country’s productive capabilities as reflected in its export structure. Countries with high complexity produce a wide range of technologically advanced goods and tend to enjoy higher and more stable long-term growth.

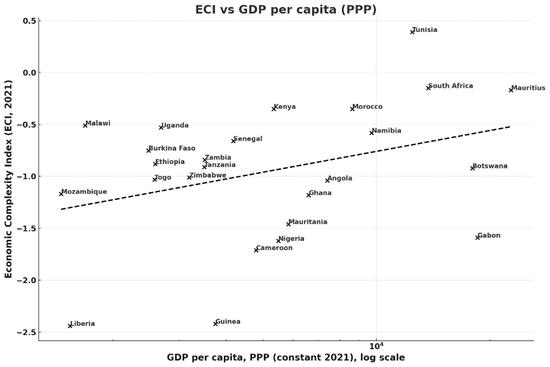

Figure 1: GDP per capita and Economic Complexity (2021)

Across Africa, economic complexity remains persistently low. With few exceptions, African exports are concentrated in raw materials, agricultural commodities, and low-value manufactures. No African country ranks in the upper third of the global complexity distribution. Even the continent’s most diversified economies—South Africa, Tunisia, Morocco, and Mauritius—remain far below the complexity levels achieved by emerging Asian economies.

This structural constraint has several consequences. First, low complexity limits productivity growth. Without dense networks of complementary skills, technologies, and firms, economies struggle to move into higher-value activities. Second, commodity dependence increases vulnerability to external shocks, as price fluctuations directly translate into income volatility. Third, low complexity constrains employment creation, as resource sectors and basic services generate few productive jobs.

Empirically, the relationship between economic complexity and income in Africa is positive but weak. Resource-rich countries can achieve moderate or even high income levels without increasing complexity, reflecting the role of rents rather than productive capabilities. Conversely, some countries with relatively low incomes but rising complexity—such as Kenya, Senegal, or Côte d’Ivoire—show early signs of diversification, though from a very low base.

The absence of industrial deepening is central to this pattern. Manufacturing accounts for a small and often declining share of GDP in most African countries, a phenomenon widely described as premature deindustrialisation. Industrial activities that do exist are frequently shallow, import-dependent, and weakly integrated into domestic value chains. As a result, learning effects and spillovers remain limited.

Even Africa’s better performers face binding constraints. Tunisia and Morocco have built more diversified industrial bases and integrated into European value chains, yet both struggle to generate sufficient employment for growing and increasingly educated populations. Growth has become increasingly jobless, underscoring the limits of partial industrialisation in a highly competitive global environment.

In sum, low economic complexity explains why growth in Africa remains fragile and volatile. Without a sustained expansion of productive capabilities and industrial depth, growth accelerations cannot be stabilised, and demographic pressures cannot be absorbed. Economic complexity thus represents not only a diagnostic indicator, but a structural ceiling on Africa’s development prospects.

4. Industrialisation and Global Value Chains: Africa Left Behind

Industrialisation has historically been the central mechanism through which latecomer economies achieved sustained growth, productivity gains, and broad-based employment. In Africa, however, this mechanism has remained weak, fragmented, and in many cases reversed. Recent evidence from UNIDO[3] confirms that Africa has not only industrialised slowly, but in several countries has experienced premature deindustrialisation—the decline of manufacturing activity at income levels far below those at which today’s advanced economies industrialised.

The share of manufacturing value added in GDP has stagnated or declined across much of the continent since the 1980s and now averages below 12–13 percent. In many sub-Saharan African countries, it remains below 10 percent. This contrasts sharply with East Asia, where manufacturing accounts for more than a quarter of economic output, and even with Latin America, which industrialised earlier and more deeply. Africa’s industrial gap is therefore not marginal; it is structural.

This weakness is closely linked to Africa’s marginal position in global value chains. The continent accounts for less than 2 percent of global manufacturing value added. Where African countries are integrated into international production networks, this integration is typically confined to low-value segments—basic processing of raw materials, assembly operations, or labour-intensive tasks with limited learning potential. Local value addition is minimal, backward and forward linkages are weak, and technological spillovers are scarce.

Even countries that recorded periods of accelerated growth failed to achieve a proportional industrial breakthrough. Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Côte d’Ivoire expanded industrial activity in textiles, agro-processing, and light manufacturing, but these initiatives remained small in scale, technologically shallow, and heavily dependent on imported inputs. Industrial policy efforts did not translate into dense domestic supplier networks or sustained productivity gains. As a result, industrialisation did not become a self-reinforcing driver of growth.

This pattern helps explain why growth accelerations proved difficult to sustain. Without a strong industrial core, growth relied on construction, infrastructure investment, commodity exports, and low-productivity services. These sectors can generate short-term momentum, but they do not create the learning dynamics, export diversification, or employment absorption necessary for long-term transformation. Industrialisation, in short, has remained the missing link between growth and development.

5. Institutions, Rent-Seeking, and Self-Inflicted Constraints

Economic structure alone does not explain Africa’s development outcomes. Institutional performance plays a decisive role in determining whether growth can be stabilised, diversified, and translated into rising living standards. The Performance Index Africa highlights profound differences in capacity building, governance quality, and institutional effectiveness across the continent.

A central finding is that many African countries significantly underperform relative to their income levels. Countries with similar per capita incomes often exhibit starkly different performance outcomes in terms of education, infrastructure, financial development, and governance. These gaps cannot be explained by geography or resource endowments; they reflect institutional choices and political economy dynamics.

Extractive institutions and rent-seeking practices are widespread. In many countries, political power is concentrated in narrow elite networks that use state authority to capture rents rather than to promote broad-based development. Public investment is often inefficient, regulatory frameworks are selectively enforced, and industrial policy is undermined by patronage. As a result, state capacity erodes instead of strengthening.

This institutional erosion has intensified since the mid-2010s. Several countries that had previously improved governance experienced setbacks due to political fragmentation, conflict, or authoritarian consolidation. Military coups, constitutional manipulation, and the weakening of accountability mechanisms have further undermined development prospects. In fragile states, institutional collapse has become self-reinforcing: insecurity weakens state authority, which in turn fuels further conflict and rent extraction.

Even in countries with comparatively strong institutions, performance remains fragile. Botswana demonstrates that good governance can ensure stability and moderate prosperity, but it also shows that institutions alone do not guarantee deep structural transformation. South Africa illustrates the opposite trajectory: relatively high income combined with declining institutional quality has resulted in stagnation and deindustrialisation.

The core implication is that Africa’s growth constraints are not merely imposed from outside. They are, to a significant extent, self-inflicted. Weak institutions, rent-seeking elites, and fragmented governance systems prevent economies from building productive capabilities, scaling up firms, and sustaining growth accelerations. Without institutional reform, even favourable external conditions fail to generate lasting progress.

6. Demography, SMEs, and the Employment Trap

Africa’s demographic dynamics magnify the consequences of weak transformation. The continent’s population is projected to continue growing rapidly for decades, with particularly large cohorts of young people entering labour markets each year.[4] In principle, this demographic trend could support growth through expanding markets and a growing workforce. In practice, it has become a source of mounting pressure.

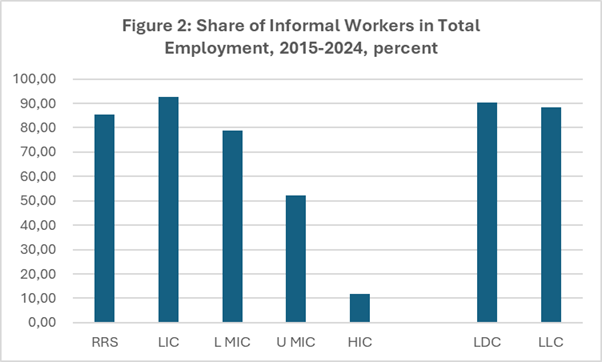

Most African economies are unable to generate sufficient productive employment to absorb new labour market entrants. Industrial sectors are too small, modern services too limited, and agricultural productivity too low. As a result, employment growth occurs primarily in informal and low-productivity activities. Underemployment, rather than open unemployment, is the dominant outcome.

Source: OECD, AfDB (2025). Explanations: RRS = resource-rich states; LIC = low-income countries; L MIC = lower middle-income countries; U MIC = upper middle-income countries; HIC = high-income countries; LDC = least developed countries; LLC = landlocked countries

Even countries often cited as relative success stories face this constraint. Tunisia, South Africa and Morocco have achieved higher economic complexity and deeper industrial integration than most African countries, yet both struggle with persistent youth unemployment and jobless growth. This illustrates a broader pattern: partial transformation is insufficient in the face of rapid demographic expansion.

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) play a central role in this employment trap. SMEs employ the majority of Africa’s workforce, but most remain informal, undercapitalised, and disconnected from larger value chains. They are too small to benefit from economies of scale, too isolated to upgrade technologically, and too constrained to expand into export markets. The “missing middle” of medium-sized, growth-oriented firms remains largely absent.

Institutional and structural barriers reinforce this outcome. Limited access to finance, weak infrastructure, regulatory uncertainty, and rent-seeking practices prevent SMEs from scaling up. Industrial clusters and supplier networks remain underdeveloped, further limiting learning and productivity gains. As a result, demographic growth translates into expanding informality rather than into a demographic dividend.

The interaction between weak industrialisation, extractive institutions, and rapid population growth creates a self-reinforcing low-level equilibrium. Growth remains volatile, employment creation insufficient, and poverty persistent. Without a decisive shift toward productive job creation, demographic pressure risks becoming a destabilising force rather than an engine of development.

Taken together, the evidence from industrialisation, institutional performance, and demographic dynamics reinforces the central argument of this paper: Africa’s development challenge is structural, not cyclical. Growth without industrial depth, institutional capacity, and employment absorption cannot be sustained. The next section therefore draws these strands together and assesses what the findings imply for Africa’s long-term development prospects.

Conclusion: Africa Is Not Failing – But It Is Blocking Itself

This paper set out to reassess Africa’s development trajectory between 2000 and 2024 through the lenses of growth accelerations, economic complexity, and multidimensional performance. The evidence leads to a clear and sobering conclusion: Africa’s central development challenge is not the absence of growth, but the persistent failure to transform growth into sustained structural change.

Africa has not been standing still. Several countries have experienced periods of rapid expansion, improved macroeconomic management, rising infrastructure investment, and, in some cases, declining poverty. Yet these advances have remained partial, fragile, and unevenly distributed. Genuine growth accelerations, as defined by strict empirical criteria, are rare. Where they occurred, they were seldom institutionalised and often reversed by political fragmentation, conflict, or adverse external shocks. For most countries, growth has been volatile, externally driven, and insufficient to raise living standards on a durable basis.

The Economic Complexity Index reveals why these growth episodes failed to translate into long-term development. With few exceptions, African economies remain locked into low-complexity production structures, dominated by raw materials, basic agriculture, and low-value services. This structural constraint limits productivity growth, increases vulnerability to global price cycles, and constrains employment creation. Income gains based on resource rents have not been accompanied by the accumulation of productive capabilities, leaving economies exposed and brittle.

Industrialisation—historically the backbone of successful late development—has not fulfilled this role in Africa. Manufacturing remains small, shallow, and in many cases declining. Africa’s integration into global value chains is marginal and concentrated in low-value segments with limited learning effects. Even the continent’s better performers struggle to generate sufficient industrial employment. Partial industrialisation has not been enough to absorb rapidly growing labour forces or to create self-reinforcing growth dynamics.

Institutional performance further explains this outcome. The Performance Index Africa demonstrates that many countries significantly underperform relative to their income levels. Extractive institutions, rent-seeking elites, and weakening state capacity undermine policy implementation, distort incentives, and prevent the scaling up of firms and sectors. In this sense, Africa’s constraints are not merely external or historical; they are largely self-inflicted. Where institutions erode, growth loses its foundations. Where governance fragments, transformation stalls.

Demographic dynamics amplify these structural weaknesses. Rapid population growth collides with economies that are unable to generate sufficient productive jobs. The result is widespread informality, underemployment, and rising poverty, even in countries that continue to grow. Small and medium-sized enterprises, which employ most of the workforce, remain too small, informal, and disconnected to drive transformation. The much-discussed demographic dividend thus remains elusive and, in fragile contexts, risks becoming a destabilising force.[5]

Taken together, the three analytical lenses converge on a single diagnosis. Africa is not failing because it lacks potential or opportunity. It is failing to converge because growth has not been anchored in industrial depth, institutional capacity, and productive employment. The popular narrative of Africa as a “future continent” obscures this reality. It conflates episodic growth with transformation and optimism with evidence.

A more realistic assessment is therefore required. Africa’s future will not be determined by growth rates alone, nor by demographic momentum, nor by external finance. It will depend on whether countries can overcome extractive political economies, build inclusive and capable states, deepen industrial and productive structures, and enable firms and workers to scale up. Without such changes, growth will remain volatile, poverty persistent, and convergence elusive.

The central lesson of this paper is thus neither pessimistic nor celebratory. It is analytical: Africa’s development challenge is structural, institutional, and industrial. Until these constraints are addressed, Africa will continue to weaken its own growth from within.

Click here for paper: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-107094-5

[1] Robert Kappel (2013): Africa: Neither Hopeless nor Rising, Hamburg. ssoar-2014-kappel-Africa_neither_hopeless_hor_rising.pdf

[2] Ricardo Hausmann, Lant Pritchett, and Dani Rodrik (2005), Growth Accelerations, in: Journal of Economic Growth 10, 4: 303–329.

[3] UNIDO (2025), Industrial Development Report 2026, Vienna. IDR 2026 - Web Report | UNIDO

[4] Jakkie Cilliers (2025), Africa’s slow development: it’s demographics, not poor governance - ISS African Futures

[5] Gary S. Fields (2023), The Growth–Employment–Poverty Nexus in Africa, in: Journal of African Economies 32, Issue Supplement_2, April 2023, Pages ii147–ii163; Robert Kappel (2021), Africa’s Employment Challenges: The Ever-Widening Gaps (2021), Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Foundation (http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/iez/18299.pdf).